Evolving Definition of Health

Health is multifaceted and hard to define. Its definition has evolved over the years to reflect new knowledge and changing global health trends. One of such significant shifts is the transition from equating health to the absence of disease to the inclusion of other dimensions of health. The World Health Organization’s definition of health emphasizes that health goes beyond the “absence of disease or infirmity”.

“a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”.

Whereas some deem the definition holistic, addressing all the relevant dimensions of health, there are contrary opinions. Some assert that the definition must be amended to accommodate additional dimensions of health such as spiritual health. In their paper titled “How should health be defined?”, Jadad and O’Grady argue that there cannot be a single definition that adequately encapsulates the complexity of health. Leonardi opines that this complexity should be embraced, and room made for the coexistence of multiple definitions of health.

In the midst of these controversies, one thing remains undebatable: the WHO’s definition of health has contributed significantly to an appreciation of the fact that health transcends biology and medical services. It has contributed to the inclusion of non-medical health determinants in health agenda and policies globally and locally. This gives credence to Leonardi’s assertion that the definition of health has implications for policy, practice and health service delivery. There is a plethora of evidence emphasizing the fact that health is shaped by non-medical factors. These factors are termed social determinants of health.

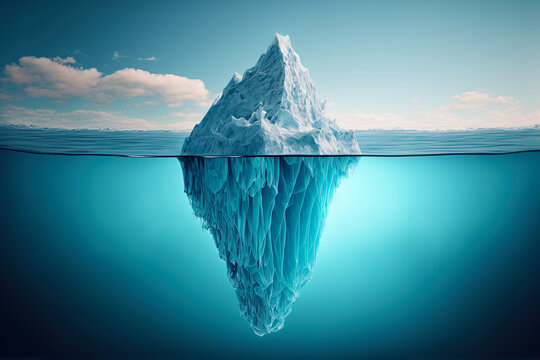

The Iceberg Effect

According to the WHO, Social Determinants of Health are “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.” Michael Marmot draws attention to the fact that these are fundamental causes of health. He employs the “causes of the causes” phrase to drum home his point that social health determinants are root causes of health outcomes.

Rightly so, the medical profile of individuals, families and communities are a ‘tip of the iceberg’. A deeper dive into their lives will most likely reveal the humongous base of the iceberg: low-income levels, low access to healthcare, poor diets, beliefs, attitudes, low access to safe water, hazardous working environments, poor housing, lifestyles. These are examples of social determinants.

Dealing with the tip of the iceberg or symptoms without addressing the root causes of health problems initiates the cycle of a never-ending health problem. Delving deeper to address the root causes may be relatively herculean. It may require more resources: time, human, financial resources. But in the long term it yields more desirable and sustainable health outcomes if the resulting interventions are efficiently planned and executed.

An Example

If it is established that a community records high rates of malaria annually, medics can repeatedly treat victims of the disease. This is necessary and may be relatively easier and cheaper to do. However, it may not be adequate to break the cycle of the disease. Hence, annual prevalence will remain high all things being equal. A more sustainable approach will be investigating factors influencing the high annual prevalence of malaria. This may for instance reveal the underlying causes such as: low awareness about malaria and its prevention, low access to insecticide treated nets, poor environmental factors and stagnant waters.

Once these are identified as the underlying causes, the problems are defined. A problem well defined is half solved. Tailor made interventions can be planned and implemented to address these underlying causes of the high prevalence of malaria. The process of investigating the underlying causes, planning and implementing solutions will be more arduous, time consuming and require more resources. In fact, it may take years to achieve desired results. But in the long run it will yield more efficient and sustainable results than just administering medications, all things being equal.

Conclusion

It is important to treat diseases medically. However, to sustainably address Public Health Problems, there is the need to understand the underlying causes of the problems and provide tailored made solutions. It may be herculean, more expensive and take longer time. But it will prove beneficial in the long term. It pays to go beneath the “tip of the iceberg”.

We shall continue discussions on social determinants in the following weeks.

Please subscribe for more.

The issues of social determinants of health are the most significant for any country’s development. However,global agenda to tackle these determinants requires political will and commitment.Unfortunately,this is lacking.The social inequality gap keep widening,the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer.Infact,I notice that in most developing countries,corruption has been the barrier to achieving any positive impact in tackling the social determinants of health.